Curatorial Statement

Outside the lines

Outside the lines is an annual exhibition showcasing works from Emerson’s extensive collection of art, artifacts, fabrics, and furniture gathered throughout his time in Zanzibar. This exhibition highlights the influences behind Emerson’s artistic and cultural vision, connecting his legacy with the foundations aim to support individuals with exceptional talents in artistic and academic fields and to assist local organizations that preserve and enhance the culture of Zanzibar.

Those who visited his hotels know Emerson’s passion for collecting art and artifacts. He was deeply inspired by the island’s rich cultural expressions, often blending Swahili art and objects with modern and foreign influences. His designs were rooted in Swahili traditions, using local materials and techniques suited to the climate and culture. Emerson’s approach was eclectic, never confined to a single tone, style, or trend. Like a skilled musician, he improvised, combining different keys and rhythms while respecting the structural beauty of Zanzibar.

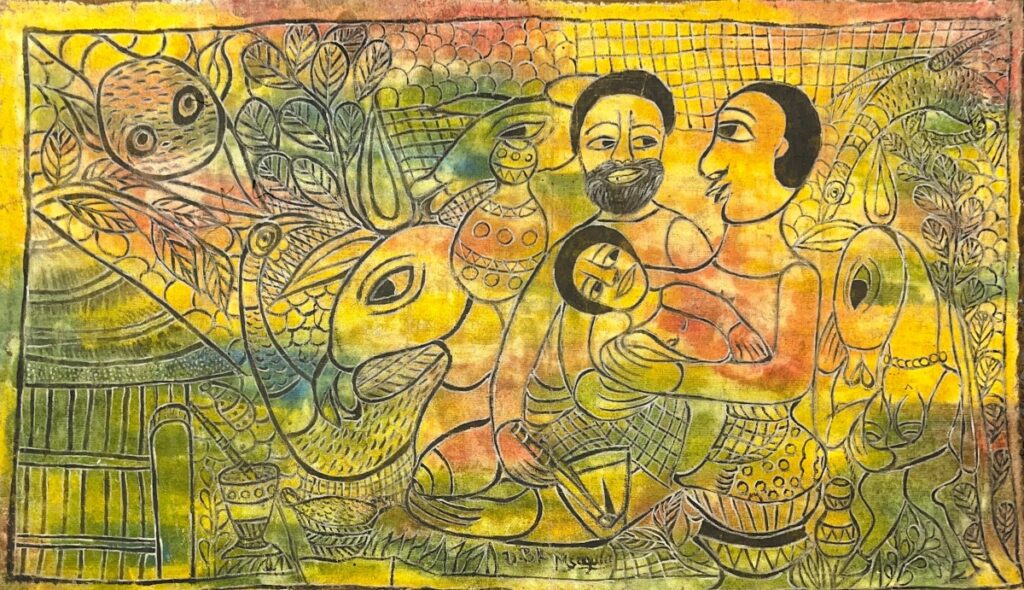

Damian B.K. Msagula (1939-2005)

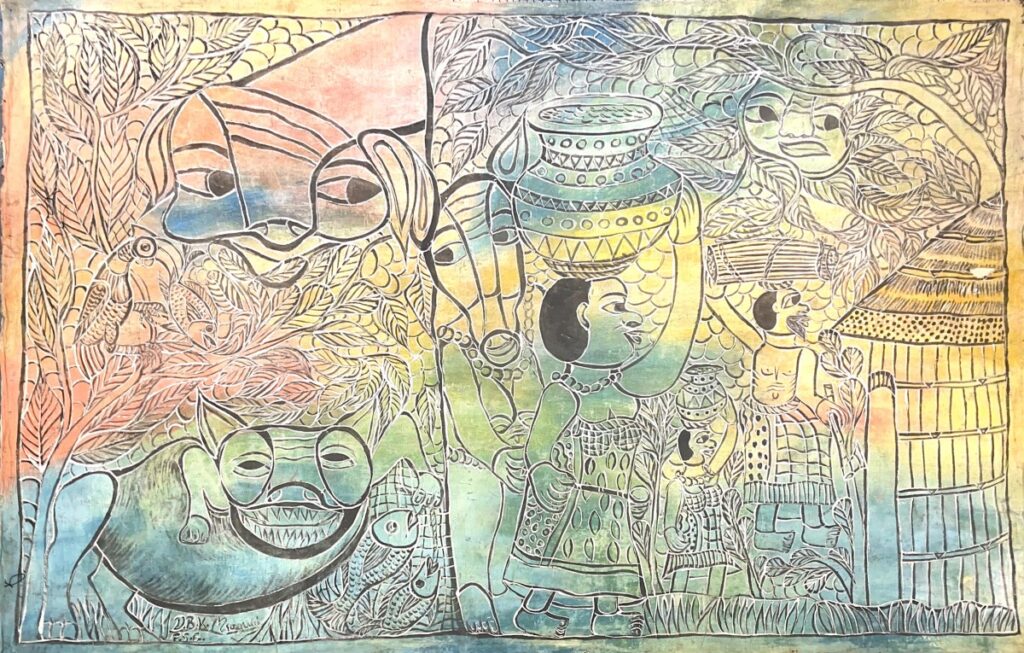

In this exhibition we present works of Damian B.K. Msagula. Not much is known about the history of the paintings in Emerson’s collection, other than that they were purchased in the late 1980s and 1990s. Msagula, originally from Ndanda in the Mtwara region, began his artistic journey with the Tinga Tinga collective in Dar es Salaam. Over time, he developed his own distinct style and became a prominent figure in the Tanzanian art scene, sharing stylistic and thematic connections with peers like George Lilanga and other artists from Nyumba ya Sanaa. Msagula’s work is known for its unique technique, where he boldly colored outside the lines.

According to historian and cultural entrepreneur Farid Fazach, Emerson was among the first to collect and share works from the Tinga Tinga style with local artists, challenging more traditional, realistic approaches. Around that same time, the Tinga Tinga collective opened its first shop in Stone Town, introducing a bold new aesthetic to the area.

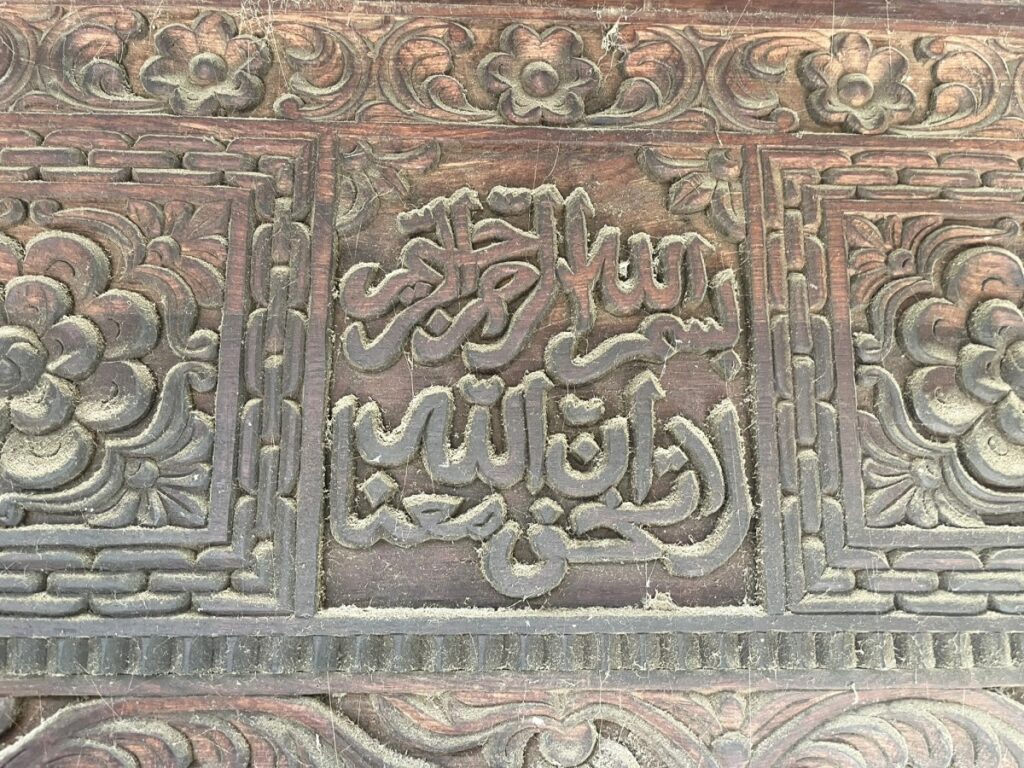

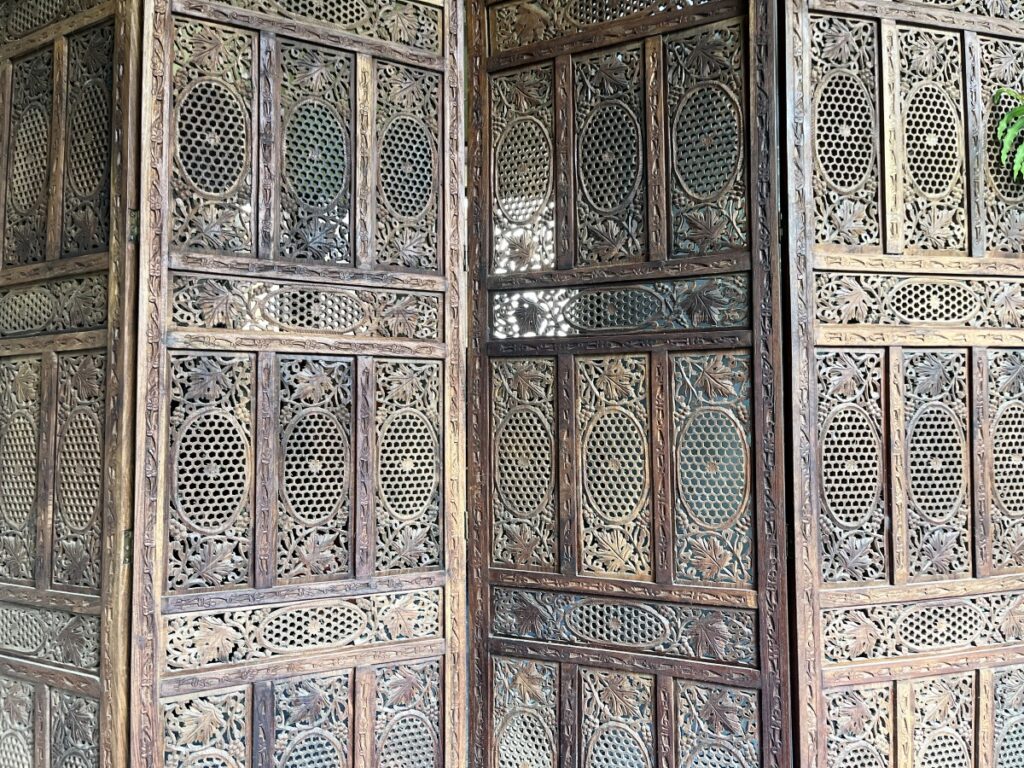

Traditional Swahili art, rooted in Islamic tradition, avoided figurative imagery, focusing instead on the beauty of carved wood, intricate geometric patterns, textile designs, and especially religious calligraphy. In contrast, the emerging mainland artists embraced depictions of people, often in rural scenes and animals, many of which aren’t native to the island.

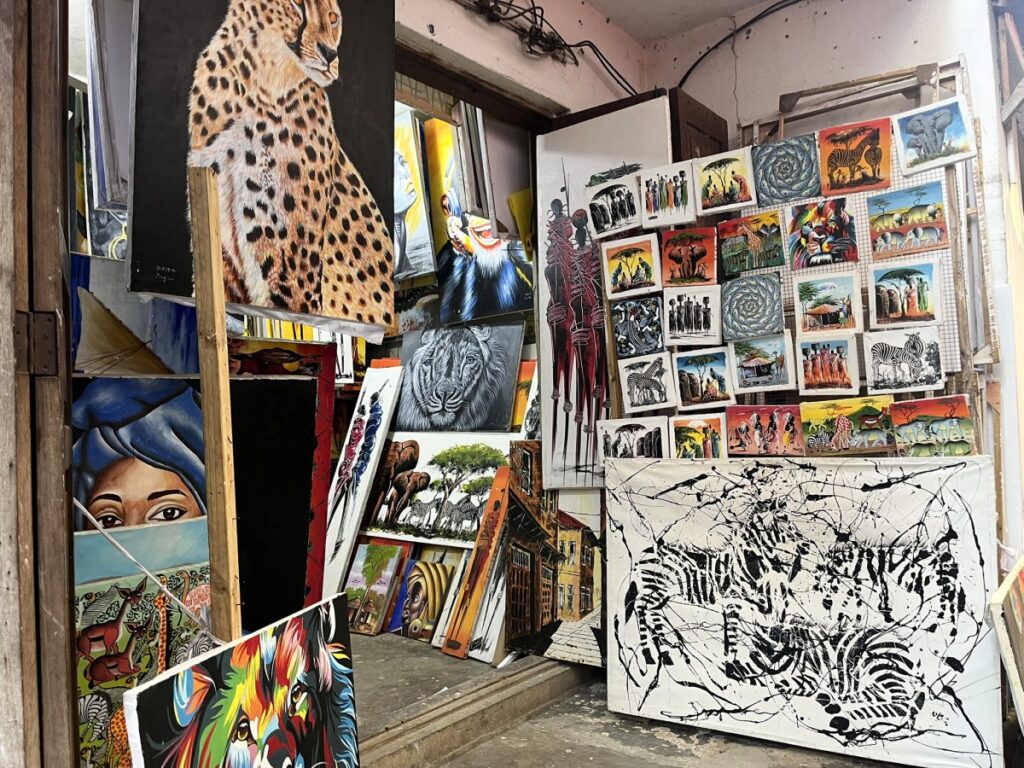

Their vivid, stylized paintings sparked a new artistic energy both on the island and beyond. Keith Haring, for instance, once cited George Lilanga as one of his key inspirations. Today, the influence of the Tinga Tinga school is unmistakable. A quick look around Stone Town’s galleries and art shops will show just how deeply this movement has shaped the local visual culture.

But beyond that, the movement he represents tells a larger story, one about the visual merging of Tanganyika and Zanzibar. Today, in shops across the island, you’ll find traditional art forms like calligraphy and wood carving displayed right alongside vibrant paintings of animals, lions, elephants, giraffes, and others that actually don’t exist on the island.

To an outsider, these images flow together seamlessly, forming at first side a single, unified picture of Tanzanian identity. But as artist Omar R. Omar aptly observed, the commercialization of culture leads to curious absurdities: a “Hakuna Matata” T-shirt, depicting jumping Maasai warriors and marked “Zanzibar” a contradiction in itself! [Considered more Kenyan than Tanzanian Swahili]. These visual cues, whether inherited or invented, from the islands or mainland, authentic or manufactured, converge to shape a shared narrative, one increasingly detached from the complex, everyday realities of Tanzanian life.

Msagula’s work holds historical weight in shaping the current art landscape together with his mainland peers, but its value extends far beyond familiar scenes of animals, people, and village life. His singular approach, rooted in innovative materials and technique, marks him as a standout figure.

We encourage you to look beyond the lines, move past the obvious and explore the deeper dimensions of his art.

Material

People often ask why artists still paint when they could simply take a photograph. But this question is somewhat simplistic: paintings and photographs are fundamentally different. That difference begins with the way each is made. A painter uses their own eyes to translate a personal vision directly onto the canvas. A photographer, by contrast, relies on a machine, a camera with a single lens, programmed by its maker, as a filter between themselves and their subject. [Read e.g. Vilém Flusser, Towards a Philosophy of Photography]. These two distinct ways of seeing inevitably produce different results, even when the final images may appear similar.

This distinction becomes even more apparent when we consider the final product. Photographs are typically printed with ink on paper, a standardized process. In contrast, painters work with a far more diverse range of materials: from pencil to collage, henna to mud. Beyond this variety, the choice of surface, canvas, paper, wood, or otherwise. is not incidental. It plays an integral role in the artwork itself, adding layers of meaning that deepen our understanding of the piece.

Take, for example, Said Tinga Tinga, who painted on plywood, or Damian Msagula, who works with two distinct types of canvas: jute and cotton. Jute is a material historically used in Zanzibar for transporting and storing cargo, making it an essential fabric in a harbor and trading city. The cotton Msagula uses is known locally as Merikani, a fabric traditionally used, among other things, for kanga’s and the sails of dhows. These same dhows once transported, and in some cases still transport, cargo packed in jute. Even today, Merikani remains a material to make canvas among painters in the region.

When viewing Msagula’s paintings, it becomes clear that similar images and colors take on distinct qualities depending on the canvas used. The rough weave of jute creates a different visual and emotional texture than the more tightly woven cotton. Jute gives the work a raw, earthy quality, while cotton produces a smoother, more refined appearance. The choice of material adds an extra layer of meaning to the artwork. This is a concept echoed by Ghanaian artist Ibrahim Mahama who gained international recognition for his use of jute sacks to tell the story of the West African cocoa trade. In his work, jute is not just a surface, it is the artwork itself.

Msagula tells his story not only through imagery, the canvas itself becomes part of his storytelling. He comes from a region where cashew farming plays a central role in both livelihood and landscape. Jute, historically used to store and transport cashew harvests, is one of the materials he chooses intentionally, reflecting this deep connection. Cashew trees are a recurring motif in his work, representing the economic life of his home. In one painting featured in this exhibition, a cashew harvest celebration is depicted, not only painted on jute, but also using natural pigments, some derived directly from the cashew nut. This piece carries three meaningful layers: the image, the canvas, and the pigment. Together, they offer a depth of narrative that extends well beyond the visual. Though his imagery may echo scenes found in the streets of Stone Town, Msagula’s deliberate material choices set him distinctly apart.

But above all, it is Msagula’s inventive approach to painting that convinced me he deserves far greater attention. There is something remarkably intuitive in the way he composes his work, an insight into how we see and perceive, that sets him apart. It is this thoughtful and original vision that makes him a great choice for the first exhibition of Emerson’s collection.

Outside the lines

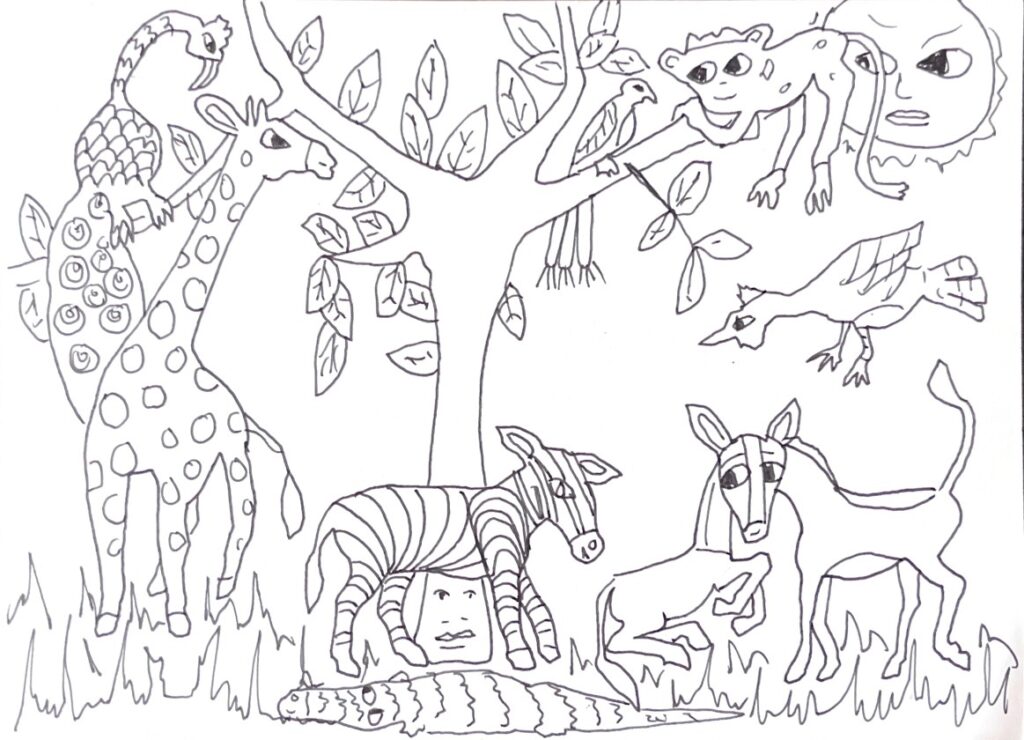

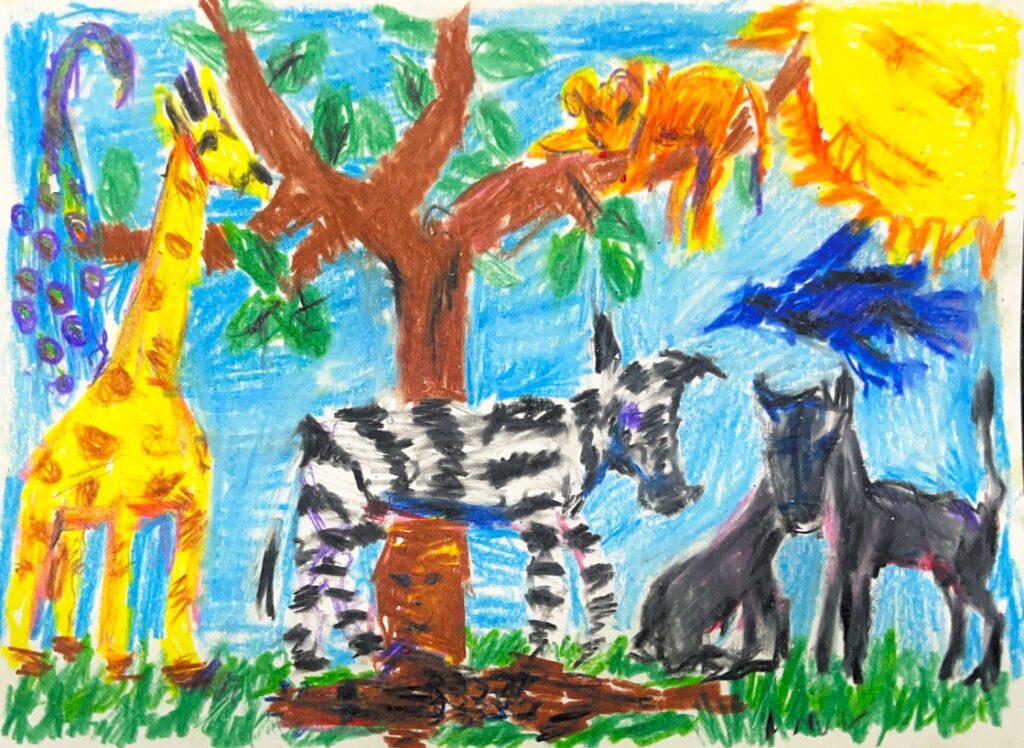

Coloring outside the lines may seem simple, but it has a profound impact on how we engage with Msagula’s work. His non-classical style is strongly connected to his peers. He painted scenes of rural life, often blending spiritual and religious elements, alongside depictions of (mainland) Tanzanian wildlife. Like Said Tinga Tinga and George Lilanga, Msagula used bold outlines to define figures in his paintings. However, it is his unique relationship between these outlines and the colors he uses that truly distinguishes him. This choice, not just in Tanzania but globally, is unconventional.

If you look around you right now, you’ll notice that nothing in physical reality has black outlines. Line drawing, a technique that uses lines without shading, is a way of transferring observations from three dimensions onto a two-dimensional surface to represent form and depth. Many of us are accustomed to the idea of coloring within the lines, a habit that makes it easier for our brains to recognize what is being depicted. But lines aren’t necessary to create figurative art, color alone can form shapes, as seen in classical oil painting. Conversely, lines can also be used to create abstract art. Msagula uses black lines, often enhanced with grey or silver, to create his figures.

Msagula’s use of color in his paintings is a key element of his distinctive style. He often works with the three primary colors—red, yellow, and blue—and their basic mixtures, such as green, orange, and brown. When you focus on the colors alone, they form abstract patterns across the canvas. What makes his work stand out is the way he combines lines and color. Rather than linking the two directly, he often deliberately avoids a direct link between the lines and the colors, allowing both to coexist in an unconventional, yet harmonious, way.

With this combination of line drawing and color, Msagula creates three layers of seeing or perception: outlined figurative images, abstract color patterns, and the interplay between the two. This uncommon technique evokes a sense of Marc Chagall’s freedom in space, but while Chagall’s colors interact with his images, Msagula work differs in its approach. His lines are structured and defined, while his colors roam more freely. This contrast forces the viewer to slow down and carefully examine the work, challenging our perceptions of what is real, surreal, or dreamlike.

In today’s world, we’re constantly exposed to images on screens, clothes, billboard etc. which are fixed and static. This can make us forget how complex the act of seeing truly is. Our eyes are not like cameras, they don’t create fixed images when we look at something. Instead, we receive light input, and our brain constructs coherent images based on our previous experiences. Art plays with this knowledge by creating illusions that are perceived as real. For example, we instinctively understand that a larger figure in a painting seems closer to us, even though it’s actually placed right next to smaller figures on the same flat canvas.

Msagula doesn’t employ classical perspective, yet his technique challenges how we perceive in a similar way. As you approach his works, let his technique be your guide. Observe the three layers he uses, follow the lines, concentrate on the colors, and appreciate how they interact. You’ll discover more than you initially thought, and as he tells his stories, you can create your own.

We invite you to take in this work with fresh eyes. Let go of assumptions, and let your gaze lead you into the layered narratives that Msagula so vividly brings to life.

Jan van Esch

Curator and artist

janvanesch.com

Emerson Dewey Skeen

Beyond opening boutique hotels, he was deeply engaged in cultural initiatives that continue to influence the island’s art scene today.

In collaboration with others, he helped launch significant projects such as the Zanzibar International Film Festival (ZIFF), the Dhow Countries Music Academy, and the internationally recognized Sauti za Busara music festival.