Damian Msagula IV & V

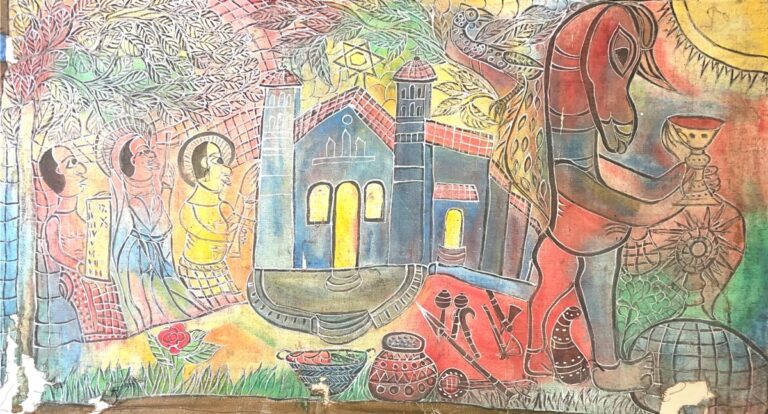

Untitled IV

Artist: Damian Boniface K. Msagula

(Tanzania, 1939 – 2005)

197 x 102 cm (approx.)

Paint (unknown) on jute

Year unknown

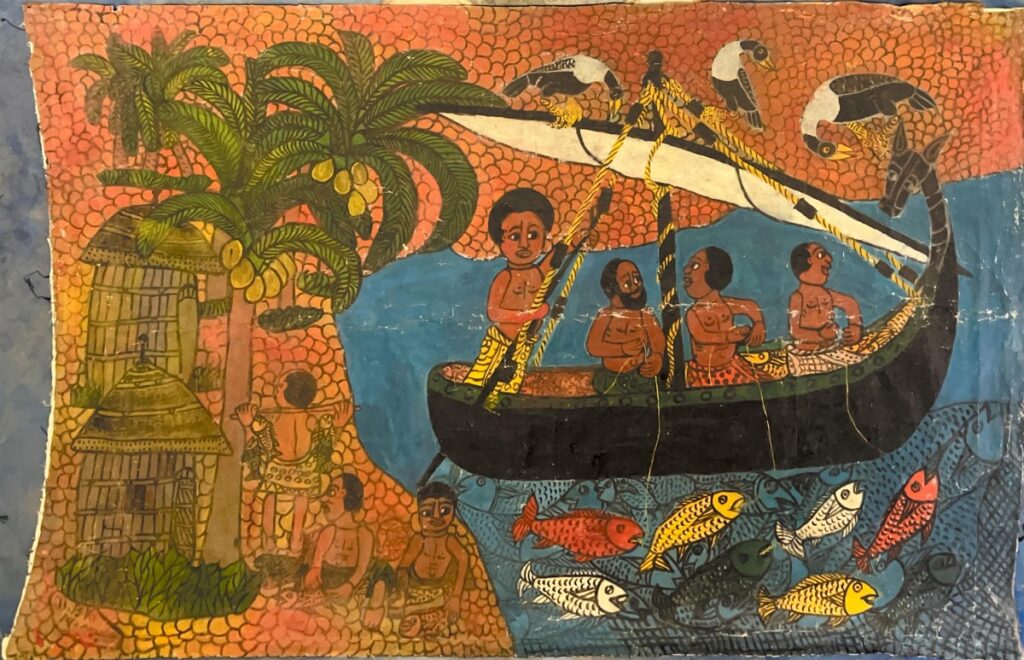

Untitled V

Artist: Damian Boniface K. Msagula

(Tanzania, 1939 – 2005)

190 x 115 cm (approx.)

Oil on canvas

Year unknown

These two paintings explore a recurring theme in Msagula’s work: the relationship between religion old and new, spirituality, and the physical versus the intangible. He opens this conversation through his distinctive interplay of lines and colors.

In Untitled IV, painted on jute, the artist deepens this exploration.

Some shapes are carefully colored in; others float in the loose relationship between line and color. What guides this distinction? At the center of the composition is a recognizable building: the Abbey of Our Lady Help of Christians, a Benedictine monastery in Ndanda, Mtwara region.

It’s clearly depicted with blue walls, a red roof, and yellow (light from) doors and windows.

Approaching it are three human figures, each accented with yellow, red, blue, and green color accents. Nearby, we once again encounter a familiar character: a donkey-headed, human-bodied figure painted in patches of red and blue. It carries a neatly colored goblet filled with a red liquid. Msagula blends Christian imagery with old religious attributes and spiritual symbols, suggesting a meeting, or perhaps a tension, between the old and new.

His technique highlights the interplay between the neatly colored-in physical and the freely colored immaterial world, yet he avoids a single interpretation.

Untitled V, along with the animal painting displayed in the lobby of Emerson on Hurumzi, demonstrates the closest connection between Msagula and the Tinga Tinga school. Both works are clearly painted using Coral house paint, a material not traditionally associated with fine art. Its fragility and tendency to break down over time further distinguish it from classical painting media.

In these works, we witness the beginnings of his distinctive color-line technique. At first glance, this may appear to be a simple, everyday scene, but Msagula offers subtle clues that suggest a deeper, more spiritual meaning.

That’s why we’ve placed it next to the painting of the Ndanda monastery.

The ship’s figurehead recalls the shetani-like figures often found in Msagula’s work. Unusually, it looks not ahead, but back towards the fishermen. Is this another moment where Msagula plays with overlapping religious and spiritual narratives?

Msagula may be drawing a link between different spiritual and religious traditions. The fishermen could evoke the disciples of Jesus.

Notably, only the fish that have been caught are painted in color—the rest remain the color of the sea. Is this a stylistic decision, or a quiet metaphor for conversion?

To bring this all into a contemporary context: do Msagula’s surreal paintings offer insight into how we experience the world today? So much of our reality is shaped by forces we cannot see or fully understand, like GPS, artificial intelligence, and other invisible systems that deeply impact our lives. Could the layered, dreamlike qualities of Msagula’s work reflect this condition, where meaning and influence are present, yet intangible?